The UN Compact as a catalyst of migration

Analysis by Szabolcs Janik and Balázs Orbán

The draft of the UN Compact issued in early February seeks to provide a comprehensive framework for the global management of migration. We should endeavor to move the negotiation process towards a compact that is much more balanced than the present version.

The positive approach suggests that taking advantage of the benefits of migration depends on appropriate “management” only. Since the draft presents migration as a positive phenomenon in and of itself, logic asserts that migratory movements are desirable (the more we have of something that is good and beneficial, the better).

Therefore, the document can act as a catalyst of future migration, while it does not differentiate substantially between irregular and regular migration, it barely refers to the importance of border protection, and almost completely disregards the challenges and social tension caused by migration. The draft of the Compact built on the interest of net source countries regarding migration forecasts serious debates in the months to come.

The context – the global migration landscape

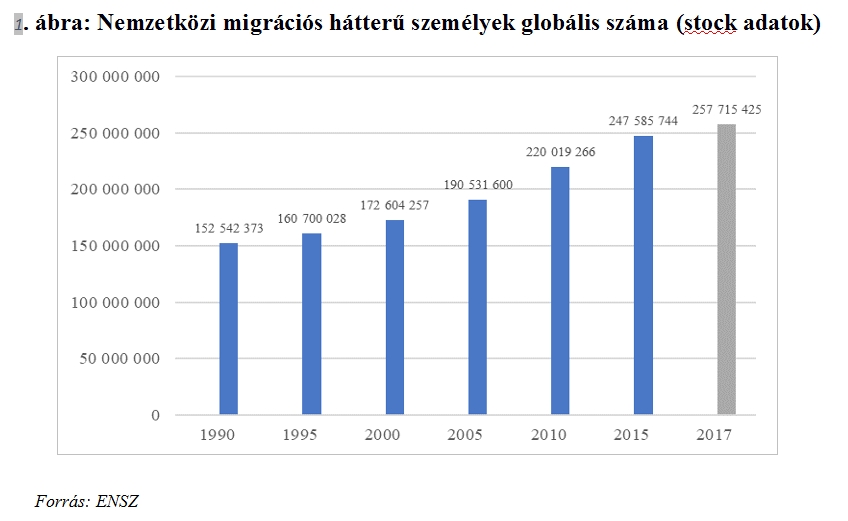

The number of international migrants has grown considerably in the past decades: according to UN estimates, their number exceeded 257 million last year (Figure 1). To grasp the tendency, it is important to note that this number was only 152 million in 1990, and 172 million in 2000. We can find highly complex reasons behind this rise of intensity in migratory movements, but the two most important drivers are most definitely the various conflicts (instability) and the economic hopelessness (insecurity).

Figure 1: Global number of international migrants (stock data)

Source: UN

The data available clearly indicates that movement within and between continents became more widespread, and an especially high number of people arrive to Europe, North America and Australia. Last year, our continent hosted almost 78 million international migrants. Of course, this also includes people migrating within the EU, but the point is that every international migrants lives in Europe.

According to the 2017 UN estimate[1], Europe is expected to face a net immigration of 32 million people between 2015 and 2050 – and this is a rather conservative estimate, which disregards several factors. The development of the desire to migrate also foreshadows the rise in future migratory movements: the global survey[2] conducted by Gallup last summer indicated that 14% (which is 710 million people) of the world’s adult population would move to another country if they had a chance (the willingness to emigrate is outstanding, 31% in Sub-Saharan Africa). In some African countries with booming populations, even more people, 40–62% of the population plan to leave their homes (Sierra Leone 62%, Nigeria 41%).

Background

The UN’s Global Compact for Migration aims to “facilitate orderly, safe, regular and responsible migration and mobility of people, including through the implementation of planned and well-managed migration policies”. This objective was also defined in the sustainable development framework adopted in 2015, but the most important precedent of the compact is the New York Declaration adopted on 19 September 2016. In this Declaration, the member states agreed to adopt two separate compacts in the future: one in relation to refugees, and one in relation to migration. Regarding the migration compact, negotiations started last spring, and in closing of the preparatory phase, a stocktaking conference was held in Mexico in December. The Secretary-General’s Report[3] published on 11 January this year was an important milestone, presenting migration as an exclusively positive phenomenon. The zero draft[4] as subject of our analysis was published on 5 February. Member states can decide on the adoption of the compact in December of 2018 in Morocco, and the General Assembly can vote on it in early 2019.

The draft of the Compact as a catalyst of migration

Although the draft of the UN Compact for Migration became somewhat more balanced in comparison to the Secretary-General’s Report it did not change substantially in content, narration or style. The text assumes that migration is an inevitable phenomenon, which must be turned into a “safe, orderly and regular” process globally.

One way to do so is the expansion of legal migration channels in order to have those who cross the borders flow from one state to another in a “smoothly”, in accordance with legal regulations, instead of irregularity. However, the draft barely differentiates between regular and irregular, i.e. between controlled and uncontrolled, legal and illegal migration movements (universal migration concept). At the same time, the text highlights the protection of international migrants’ human rights exclusively, while barely referring to the countries’ sovereignty and the importance of border control.

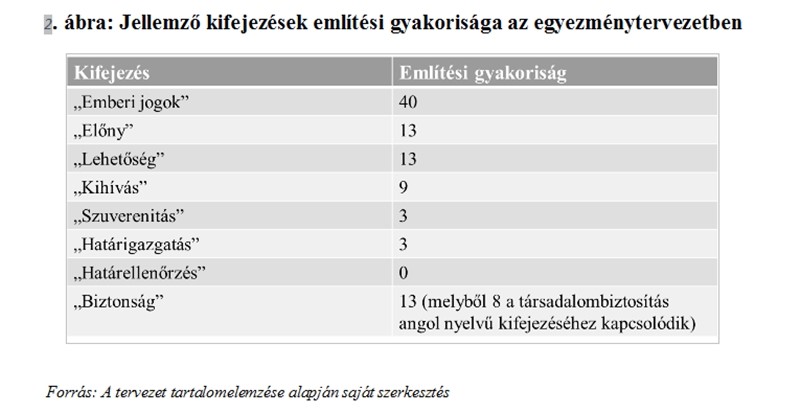

The document’s one-sidedness is reflected by the fact that the expression “human rights” appears forty times in the text, while the word “sovereignty” appears only three times, and “border control” is missing completely. The table shown in Figure 2 indicates the number of mentions of typical expressions in the draft.

Figure 2: Number of mentions of typical expressions in the draft

Source: Based on our own content analysis of the draft

There is a fashionable over-simplification among those expressing their opinions in migration issues (politicians, journalists, specialists), a professionally rather unacceptable one, which holds that migration is a positive phenomenon in every case. The UN draft evidently falls into this professional mistake. It is worth to stop here for a second, and look at what the scientific literature on migration says: is migration positive or negative in itself? In fact, raising the question this way is wrong to start with, but if we wanted to answer it, we would say “it depends”. World-famous British economist Paul Collier’s book[5] published in 2013, entitled “Exodus – How migration is changing our world”, in which he seeks to answer this question.

According to Collier, migration cannot be assessed (as positive) in general. When assessing migration, we must investigate how the social costs of the process relate to its possible gains, and this can be projected on both the source and the host countries. The author says that the number of arrivals and departures is of key importance. Collier is convinced that mass migration is explicitly harmful to both the source and the host countries. It is no coincidence that the British scholar advises the developed host countries to tighten their immigration policies. Overall, all migratory movements should be analyzed in themselves, and – despite the methodological limitations – we should seek to involve all possible aspects (economic, security, cultural, religious) in the analysis. The UN document completely ignores these considerations and puts all migratory movements on the same footing.

The draft of the Compact has another serious flaw: it does not in essence refer to the local social and cultural tensions that may evolve upon (irregular) migration, and the related security challenges (or how they should be addressed). In addition, it refers to the needs of the labor market as a reason for migration but does not touch upon the – often very negative – economic consequences experienced in the (source, transit and host) countries involved in the process. The “pro-migration” nature of the text comes to the surface in several aspects. For example, there is no strategic vision of how a viable future could be ensured to the people concerned in their homeland. Therefore, it is not surprising that no obligation to provide appropriate living conditions is put into international law. This means that the draft – despite all those in favor – does not lay down an obligation for the countries to provide local help for the source countries.

The draft leaves two important impressions in the reader. On the one hand, focusing on human rights implies that the right to migrate is a unique human right from among the new generation of human rights, and an orderly framework should be established for its exercise. On the other hand, the document can be viewed as a step towards the global governance of migration, pushing the nation-state competence into the background.

On the whole, the draft of the UN Compact can be defined as a unique catalyst of migration in its present form, as it holds that (i) migration is an inevitable phenomenon, and (ii) taking advantage of its benefits depends on appropriate management and attitude only. Surely, we need more of what is good, beneficial, and promises prosperity.

The future adoption of the Compact – prospects

Member states can adopt the UN Compact for Migration in December 2018 in Morocco, at an intergovernmental conference. Then, the UN General Assembly is expected to vote on it in early 2019 (each member state has equal vote). The prognosis indicates that serious debates can be expected about the text of the Compact under way between the net source and host countries. In this regard, the EU countries in host position are potential allies, but worrisome opinions have emerged to date on the part of some member states and EU officials during the development of the EU’s negotiation position. These indicate that the position taken will greatly resemble the interests of the source countries (while how much these interests are properly defined or well-established is rather questionable). Figure 3 indicates the continental distribution of international migrants: the continents with green as a dominant color (North America, Europe and Oceania) are net host areas, while orange as a dominant color indicates net source areas (Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean).

Figure 3: Number of international migrants per continent (stock data)

Source: UN

It is also clear to see that the net source continents can in themselves form a majority in the General Assembly: 54 African and 55 Asian countries will have the opportunity to vote on the Compact. The table in Figure 4 groups the continents with regards to their migration balance, also including the number of countries, respectively.

Figure 4: Classification of continents according to their migration balance*

*Note: the number of countries in that continent are in parentheses

Source: Own compilation based on UN data

The compact will not be legally binding, but it will be suitable for producing so-called indirect legal effects in the future. The literature on international law calls this phenomenon “soft law”. In practice, this means that decisions adopted by international organizations (including UN resolutions) can serve as references or be incorporated into customary law. Hence, people arguing that the drafting process has nothing at stake are wrong – moreover, the opposite is true.

The Hungarian interest

The Hungarian interest seems clear at the moment: we should try to influence the text of the draft substantially and seek to move the negotiation process towards the birth of a compact that will be much more balanced than the present version. Beyond doubt, it could also be argued that we should “leave the table” (as the United States led by president Trump did). However, that would carry the risk of a text born without involving the position of countries critical of migration.

This could cause a serious problem in the future if the compact becomes a reference, and can thus have an adverse effect on the maneuvering abilities of countries critical of migration (as indicated above, this is a realistic scenario in the practice of international law). The avoidance of such a negative outcome is certainly worth to work for.

The analysis was originally published on: Mandiner

Date: 7 March 2018

[1]https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/Publications/Files/WPP2017_KeyFindings.pdf?utm_source=mandiner&utm_medium=link&utm_campaign=mandiner_201803?utm_source=mandiner&utm_medium=link&utm_campaign=mandiner_201803

[2]https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/Publications/Files/WPP2017_KeyFindings.pdf?utm_source=mandiner&utm_medium=link&utm_campaign=mandiner_201803?utm_source=mandiner&utm_medium=link&utm_campaign=mandiner_201803

[3]https://refugeesmigrants.un.org/SGReport?utm_source=mandiner&utm_medium=link&utm_campaign=mandiner_201803

[4]https://refugeesmigrants.un.org/sites/default/files/180205_gcm_zero_draft_final.pdf?utm_source=mandiner&utm_medium=link&utm_campaign=mandiner_201803

[5] https://www.amazon.com/Exodus-How-Migration-Changing-World/dp/0190231483?utm_source=mandiner&utm_medium=link&utm_campaign=mandiner_201803